Homestay in Kakuda: The Town of Rice and Dreams

Homestay in Kakuda: The Town of Rice and Dreams

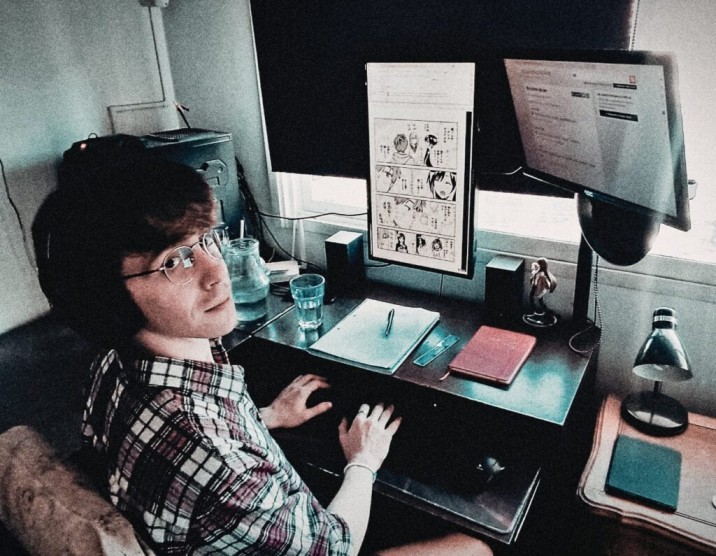

This time of the year, a few years back, I found myself in the tiny town of Kakuda, a small town tucked in Japan’s northern countryside. I stayed there with a local family, part of a university homestay program designed to connect international students with rural Japan. Today, homestays are once again becoming popular among solo travellers seeking genuine cultural immersion. Here’s what that week among rice fields and new friends taught me.

The homestay

As part of my Japanese class as a MEXT Research Student at the Tokyo Institute of Technology, a pair of international students was assigned to a family in Kakuda for a week. The remote setting offered locals a rare chance to meet foreigners and share their way of life. We joined in daily chores, cooked together, entertained the children, practised Japanese, and exchanged stories from our own countries. The itinerary also included school visits, craft workshops, and local art performances—an ideal recipe for cultural immersion.

Our host families greeting us

I was assigned to a charming family consisting of two parents, two daughters, two grandparents, and two cats, all living in a spacious yet cluttered wooden house situated in the middle of their ancestral rice fields. While the father workedat a local factory, both he and his wife, along with the grandparents, took care of the field work. Despite none of the adults or the daughters being proficient in English, we found ways to communicate. I even picked up on the Tohoku-ben, the regional accent, characterized by the suffix “-ppe” at the endof sentences, like “iku-ppe” instead of “ikimashou” (meaning “let’s go”). SinceT ohoku is one of the poorest and less developed regions of Japan, a lot of people felt ashamed of their accent and tried to hide it when moving to Tokyo, in stark contrast to Osaka people who proudly carry their accent.

Food quickly became the heart of our exchange. Every morning we helped the mother prepare breakfast—usually rice with salmon or fried cabbage and soybeans, neatly served on small plates. One evening, I cooked a Greek meal of eggplants in tomato sauce with cheese and a simple salad. When I reached for raw onions and peppers, the mother gently advised me to use a milder variety; the grandfather disliked them. I soon learned that most Japanese prefer their vegetables cooked rather than raw. The father proudly demonstrated how they polish their own rice, explaining every step from harvest to washing. Meanwhile, the grandfather poured us potato shochu and talked about his side-gig as a wild boar hunter—a conversation that left me both intrigued and slightly uneasy.

The family placed great value on privacy, refusing to share any photos of their home online—a rarity today’s digital age. Yet, one custom surprised me: everyone in the house shared the same bathwater. It basically the equivalent of a home onsen, a natural hot spring spa. After showering clean, each person took a turn soaking in the hot tub, covered afterward to keep the water warm for the next.They kindly offered me the first turn after the children, but I politely declined, explaining that in my culture we usually shower instead of bathe.

A few words about the city of Kakuda

Kakuda (角田市) is a small town in Miyagi Prefecture, part of the northern Tohoku region, with fewer than 30,000 residents. Once known for silk production, it now balances small industries with rich farmland. The town’s motto is the 5-me —Kome, Mame, Ume, Yume, Hime (米豆梅夢姫 - rice, beans, plums, dreams, princess)—reflects both its produce and its spirit. The first three elements are evidently associated with the town’ slocal produce, particularly Miyagi’s renowned rice.

The term “Dreams” in the motto alludes to the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency(JAXA) SpaceCenter located in Kakuda. This center serves as a hub for research and development in rocket engines, housing an important propulsion laboratory, and preparing engines for the H-IIA and other launch vehicles. The space center, open for free visitation, showcases various exhibits, from rocket models at scale to mechanical parts of experiments and the signatures of renowned astronauts.

The reference to “Princess” in the city’s motto represents Princess Muu (牟宇姫), the second daughter of Prince Date Masamune (you can read about him in my article about Matsushima).She is usually depicted with a crescent moon symbolizing the Date clan and a flying crane, the symbol of the Ishikawa clan to which she was married off to. Princess Muu was known for her affinity for writing and ink brushes. Legend has it that Lord Ishikawa was so enamored with the young princess that he penned329 letters to her.

Local productsare usually decorated with the famed Date crescent moon

Apart fromexploring the space center and delving into the history of the Date clan, weengaged in a flurry of other events during our trip. During the week, the towncommittee hosted a cultural dinner where students and locals shared shortpresentations. I spoke about Olympia and the Olympic flame, which had recentlypassed through Tohoku. My host family’s daughters stole the show with theiradorable dance to the then viral children’s song “Paprika.” Later, we watched atraditional Tengu dance accompanied by taiko drums, believed to bringprosperity to the community.

We, the international students, dedicated a day to visiting the local elementary school, which was relatively small, hosting approximately 10 students per class. During our time there, we participated in an English lesson led by a Canadian teacher who, admittedly, seemed to feel a bit isolated in the town. As part of their educational routine, students took turns serving lunch and cleaning up the classroom themselves. Each day, a different student puts on a large chef hat and serves soup to the rest of their classmates. It’s such a big responsibility, so their performance is top notch! We joined the students at their small desks, sharing a simple lunch together. Despite the teachers and parents’ best efforts to provide a great educational experience, I could observe the challenges faced by a countryside school, drawing parallels to my own upbringing in a rural town. This is precisely why events like our homestay hold great significance and prove immensely helpful in shaping the perspective for children growing up far from big cities.

Trying our calligraphy skills with students

Another day was dedicated to mastering the art of soba making. Soba noodles, a fundamental element of Japanese cuisine, are deceptively simple in their ingredients, yet crafting a perfect batch requires skill. We visited a soba restaurant, the Yamanouchi Bunko (そば処 山の内分校), which apparently is open only twice a month. Isn’t that curious? We were divided into teams and started the process of mixing, kneading, and, most importantly, cutting the noodles under the guidance of the skilled soba masters. In the end, both our handmade noodles and those crafted by the restaurant staff were served in a hearty meal. Dare to guess who won?

Before leaving, we visited Yamamoto Cho, a coastal town still bearing the scars of the 2011tsunami. Seeing the remnants of destruction a decade later moved me deeply. I won’t hide it, I sobbed. That visit reminded me that cultural exchange is not only about joy—it is also about empathy, understanding, and memory.

My week in Kakuda was filled with friendship and discovery. From shared meals to local customs, every moment in Japan’s countryside was truly special. I still send New Year’s postcards to my host family and follow their lives online. If your path ever leads to Miyagi, make a stop in Kakuda—and if you can, experience the quiet wonder of a homestay yourself as a MEXT scholar.